Etymology: An insult becomes THE insult

German: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP) = “National Socialist German Workers’ Party” (1920)

The abbreviation: Natsionalsozialist → “Nazi”

But here’s what matters: It was already an insult.

Pre-Hitler Bavaria: “Nazi” = diminutive of Ignatz (common Catholic name in Southern Germany). Meant: backwards peasant, rube, hillbilly, dimwit. “Haes Nazi!” (“Hot Iggy!”) = what you’d yell when you burned yourself.

When Hitler’s party emerged from Bavaria in the 1920s, opponents—especially Protestant Northern Germans—seized the existing slur. Calling them “Nazis” mocked them as stupid Bavarian hillbillies playing dress-up politics.

Hitler banned the word.

The party called themselves Nationalsozialisten internally. Used Parteigenosse (party comrade) among members. Never “Nazi.” Goebbels tried reclaiming it once in 1926 with a pamphlet called “Der Nazi-Sozi.” They gave up quickly.

When they took power: banned outright.

How it spread: German exiles made it global

Jews, communists, socialists, intellectuals fleeing Hitler in the 1930s-40s carried “Nazi” internationally—as a slur, as a warning, as the name for the thing trying to kill them.

It caught on everywhere. After WWII, it came back into Germany from outside.

The Soviets refused to use it after 1932. Didn’t want to taint the word “socialist.” Only called them “fascists.”

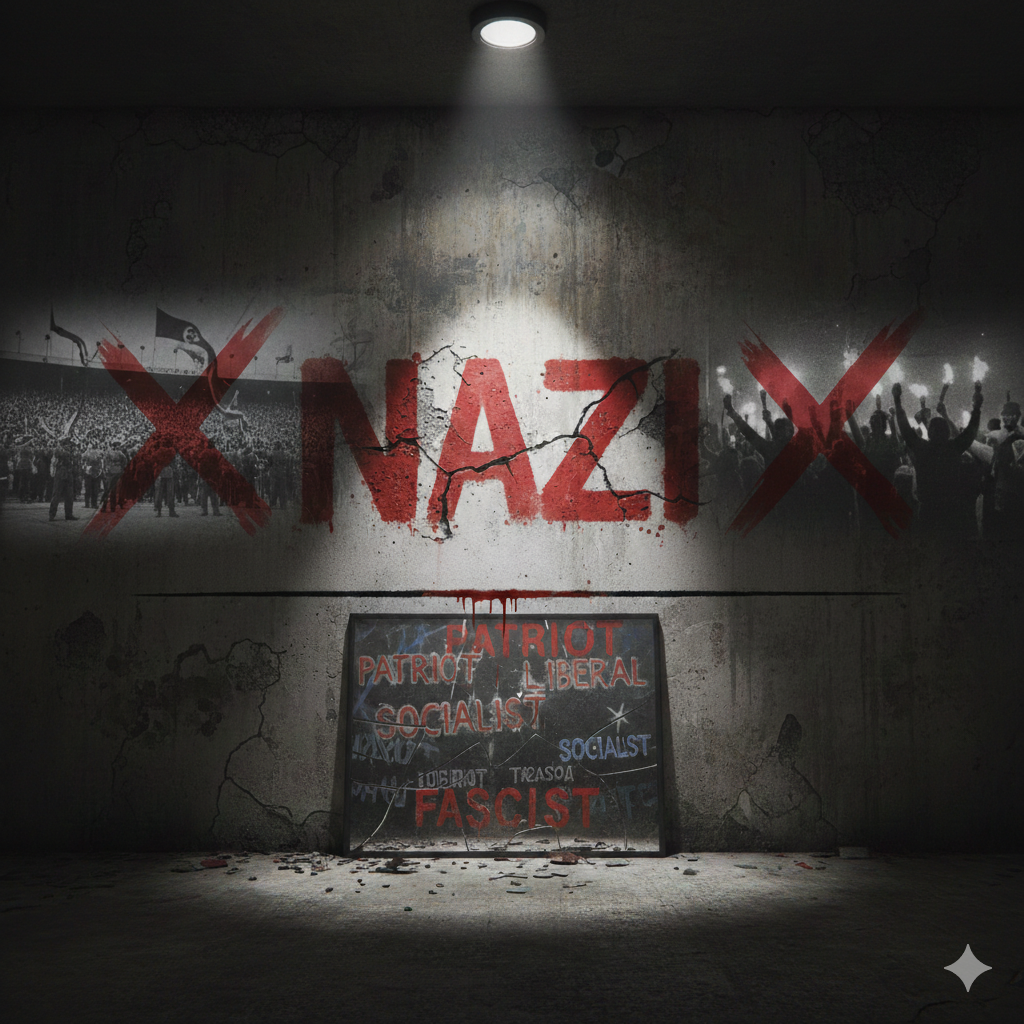

The unique pattern: It stayed stable

Unlike:

- “Patriot” (stripped through promiscuous use—everyone claims it)

- “Liberal” (inverted then poisoned—classical to progressive to insult)

- “Socialist” (evacuated—replaced “workers own production” with “government does things”)

- “Fascist” (diluted—became “authoritarian I dislike”)

“Nazi” remained:

- An insult from the start

- Rejected by the party itself

- Spread as a slur against them

- Accurate descriptor of Hitler’s specific ideology/movement

The word didn’t invert. Didn’t get evacuated. Didn’t become promiscuous.

It stayed sharp. Stayed specific. Stayed weighted with historical gravity—six million Jews, eleven million total in the camps, sixty million dead in the war.

Which is precisely what makes it complicated now.

The post-war dilution

By the 1990s: “grammar Nazi,” “soup Nazi,” “feminazi.” Godwin’s Law (1990): “As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one.”

Corollary: First person to invoke Nazis loses the argument.

The weight became a weapon. Accuse someone of Nazi behavior → automatic delegitimization. Too serious. Too extreme. You’re being hysterical.

Except.

The current paradox

The word is simultaneously:

Too serious (Holocaust gravity) to use casually

Too diluted (thrown at everyone) to be taken seriously

Still the most accurate descriptor for certain movements, rhetoric, ideology

The strategic deflection:

“You call everyone you disagree with a Nazi. The word has no meaning anymore.”

Often true. “Nazi” gets thrown at:

- Republicans generally

- Trump supporters generally

- Anyone right of center

- Sometimes people who are just rude or authoritarian

But also strategic evasion:

When actual Nazi ideology appears—ethnonationalism, blood-and-soil rhetoric, conspiracy theories about Jewish puppet masters, white genocide fears, eliminationist language toward immigrants and minorities, tiki torches chanting “Jews will not replace us”—the same deflection appears:

“You’re just calling everyone Nazi again.”

Heather’s deflection versus characteristics that fit:

“Like being called Nazi” becomes the shield. But what happens when:

- The rhetoric explicitly invokes replacement theory (Nazis: Jews replacing Aryans / Now: immigrants/minorities replacing whites)

- The symbology deliberately echoes (tiki torches, brown shirts, red armbands, certain salutes)

- The ideology centers on ethnic purity and hierarchies

- The solution involves mass deportation, camps, elimination

- The enemy is simultaneously weak (degenerate) and powerful (controlling everything)

At what point does “you’re just calling everyone Nazi” become the more dangerous evasion than overuse?

Charlottesville: When the tension became undeniable

August 2017. “Unite the Right” rally. Literal tiki torches (Nuremberg lite). Chanting “Jews will not replace us.” Nazi salutes. Confederate and Nazi flags side by side. One woman murdered.

Presidential response: “Very fine people on both sides.”

The deflection at scale: These aren’t Nazis, they’re just concerned about their heritage, about immigration, about being replaced. Some bad actors, sure, but don’t call the whole movement Nazi.

The pattern revealed:

Not everyone worried about immigration is a Nazi.

Not everyone at that rally was a Nazi.

But some of them were—explicitly, deliberately, proudly.

And the strategic conflation—lumping the explicit Nazis with the merely-concerned—protected the Nazis while delegitimizing anyone who named them.

The deflection became: If you call any of us Nazi, you’re calling all of us Nazi, therefore the word is meaningless, therefore you can’t call any of us Nazi.

The weaponization: False equivalence as shield

The corruption of “Nazi” isn’t like other words. It didn’t invert or evacuate.

It weaponized through false equivalence:

“You called my anti-immigration stance Nazi, but I’m not rounding up Jews, so clearly you’re hysterical and the word means nothing.”

True statement (you’re not rounding up Jews) weaponized to obscure true patterns (but you are echoing the same ideology that led there).

Meanwhile:

- Replacement theory → mainstream political rhetoric

- Camps for immigrants → built, defended as necessary

- Dehumanizing language → normalized

- Political violence → increasingly acceptable

- Strong leader worship → required loyalty test

Not 1933 Germany. Not identical. But rhyming enough that naming the pattern isn’t hysteria.

The distinction problems

“Nazi” vs “neo-Nazi” vs “fascist”:

Used interchangeably when politically convenient. Separated strategically when needed.

“He’s not a Nazi, he’s a neo-Nazi” (as if that’s better)

“He’s not a Nazi, he’s a fascist” (as if there’s daylight)

“He’s not a fascist, he’s just nationalist” (as if nationalism never goes ethnic)

The splitting allows precision-trolling: “Actually, Nazis were specific to 1930s-40s Germany, so calling modern white supremacists ‘Nazis’ is historically inaccurate.”

True in the narrowest sense. False in every way that matters.

Actual neo-Nazis exist.

Richard Spencer. Atomwaffen Division. The Base. Proud Boys (some factions). National Socialist Movement. Identity Evropa. Groups explicitly organizing around white ethnostate fantasies, explicit antisemitism, Nazi symbology, calls for racial holy war.

Not hidden. Not subtle. Not metaphorical.

And they count on the promiscuous use of “Nazi” to provide cover.

When everyone from Mitt Romney to Mitch McConnell to random conservatives gets called Nazi, actual Nazis fade into the noise. The word’s dilution protects them.

The accuracy problem

When is it accurate?

If someone:

- Advocates for ethnic ethnostate

- Uses Nazi symbology deliberately

- Espouses racial hierarchy

- Promotes conspiracy theories about Jewish control

- Calls for elimination of “inferior” groups

- Denies or minimizes the Holocaust

That’s a Nazi. Neo-Nazi if you want precision. But Nazi isn’t inaccurate.

When is it promiscuous?

If someone:

- Votes Republican

- Wants border security

- Opposes specific policy

- Is generally conservative

- Is just an asshole

That’s not a Nazi. Calling them one weakens the word for when it’s needed.

The stakes of getting it wrong:

Overuse → boy-who-cried-wolf → people stop listening → actual Nazis operate freely

Underuse → normalize the ideology → “just asking questions” → pipeline to radicalization → by the time we’re willing to name it, it’s entrenched

The test: Does the ideology fit?

Not: Are they literally Hitler?

Not: Are they rounding up people today?

Not: Are they in 1940s Germany?

But: Does the core ideology match?

Nazi ideology (simplified):

- Ethnonationalism (nation defined by ethnic purity)

- Racial hierarchy (some groups superior/inferior)

- Conspiracy (enemies simultaneously weak and controlling everything)

- Scapegoating (blame one group for all problems)

- Eliminationism (solution requires removal/destruction of the enemy)

- Strong leader cult (leader above law, embodies the nation)

- Militarism and violence (as purifying force)

When you see those patterns emerging, naming them isn’t hysteria. It’s pattern recognition.

And when the deflection is “you call everyone Nazi,” ask: What would count? What would you need to see before the word was appropriate?

If the answer is “literal Holocaust in progress,” the word has become useless—which means we’ve lost the warning system entirely.

Pattern summary: The corruption of resistance

“Nazi” didn’t corrupt the way other words did.

It didn’t invert (still means the same thing).

It didn’t evacuate (still connected to historical reality).

It didn’t go promiscuous through embrace (no one claims it proudly except actual Nazis).

It corrupted through strategic deflection:

Make the word so serious that using it seems hysterical.

Make it so overused that it seems meaningless.

Then occupy the space between: Serious enough that naming is dangerous, diluted enough that naming is dismissed.

The result:

Actual Nazi ideology creeps in while we argue about whether it’s appropriate to name it.

The word that stayed stable—the one that didn’t invert or evacuate—gets weaponized through false equivalence and precision-trolling.

And the people most invested in the deflection are often the ones the word most accurately describes.

Unlike “patriot” (stripped) or “liberal” (poisoned) or “socialist” (evacuated):

“Nazi” got paralyzed.

Still accurate. Still available. Still weighted with the gravity it should carry.

But trapped in a false equivalence: Either everyone’s a Nazi (so no one is) or no one’s a Nazi until the camps are operational (so by then it’s too late).

The pattern underneath:

When naming the thing is treated as worse than being the thing, the word has been successfully weaponized—not through corruption of meaning, but through corruption of the ability to use it.

And that might be the most successful corruption of all.

Because the word still works. We just can’t say it.

Or: We can say it, but only after it’s too late to matter.

The question that remains:

If “Nazi” is too serious to use casually but too diluted to use seriously, and if both overuse and underuse serve the same function (protecting actual Nazi ideology from identification), then what the hell do we do with the word?

Maybe this: Use it precisely. Use it rarely. Use it when the ideology actually fits—not when someone’s just conservative or rude or wrong.

And when someone deflects with “you call everyone Nazi,” ask: Do you want me to name the pattern, or wait until it’s undeniable?

Because history suggests that by the time everyone agrees it’s appropriate to say “Nazi,” the Nazis have already won.