The research reveals that tribal politics fundamentally reshapes how Americans process political violence, creating predictable patterns of double standards, selective empathy, and motivated reasoning that have remained consistent across centuries of American political conflict. These responses follow psychological mechanisms that prioritize group loyalty over democratic norms, threatening the foundations of pluralistic democracy.

How tribal identity overrides democratic principles

Academic research demonstrates that political identity in America has become increasingly “sorted”—where party affiliation aligns with multiple other identities including race, religion, geography, and culture. Northwestern University research reveals that out-party hatred now exceeds in-group solidarity, with Americans’ voting behavior driven more by contempt for opponents than support for their own side.² This creates what political scientist Lilliana Mason calls “uncivil agreement”—where citizens alter their policy opinions to match partisan identity rather than choosing parties based on policy.³

The psychological mechanisms are profound. Henri Tajfel’s minimal group paradigm research shows humans form strong in-group loyalties instantly, even when group assignment is arbitrary. In politics, these dynamics become supercharged. Dan Kahan’s research on “identity-protective cognition” reveals that people process information to protect membership in valued social groups, making beliefs serve social rather than accuracy functions.⁴ Citizens become what researchers call “partisan press secretaries”—defending their group’s positions regardless of evidence.⁵

When political violence occurs, these mechanisms create predictable response patterns. Research consistently shows that Americans apply different standards for political violence based on partisan alignment. The Carnegie Endowment found that having an aggressive personality is the strongest predictor of justifying political violence across parties, but political leaders play crucial roles in normalizing violence and directing anger toward specific targets.⁶

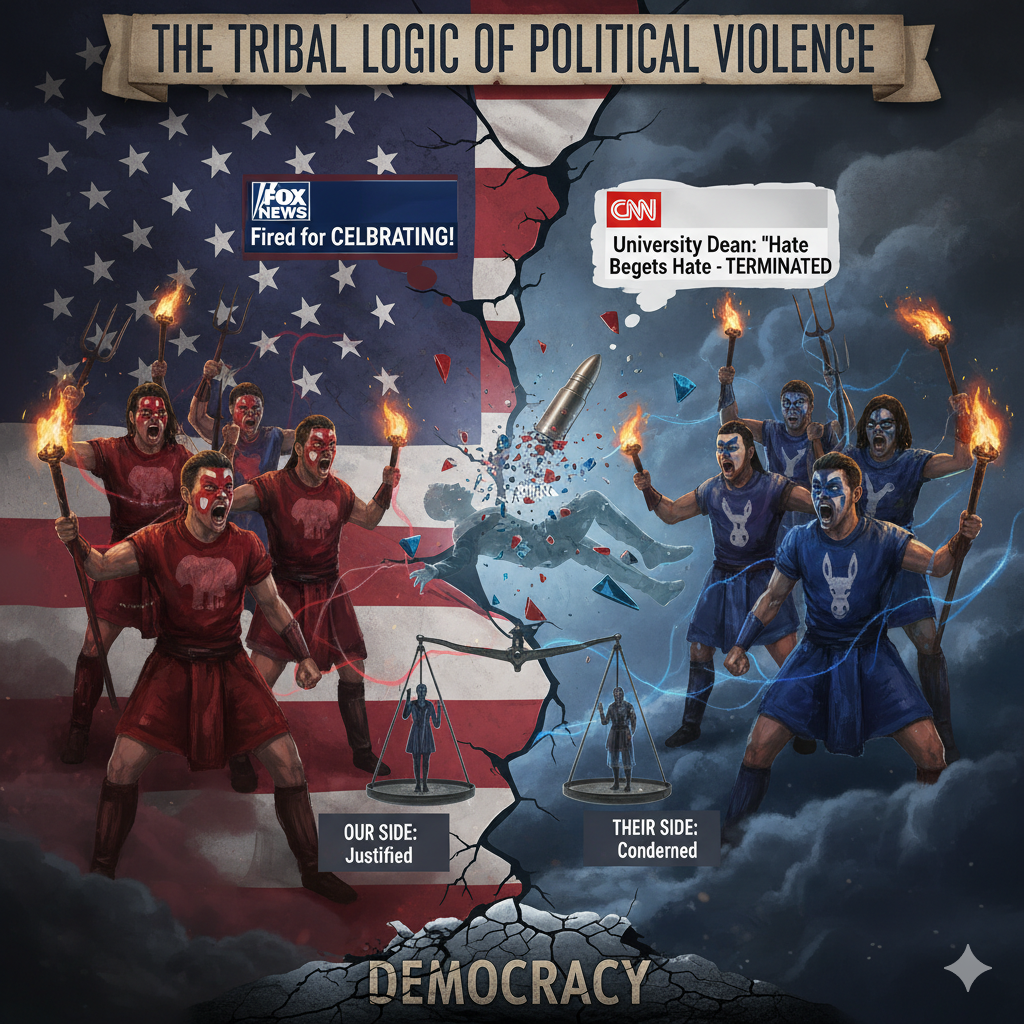

The architecture of selective outrage

The Kirk case illustrates documented double standards in how consequences are applied for similar speech. Multiple individuals faced immediate termination for comments celebrating or justifying Kirk’s death—often using rhetoric similar to Kirk’s own documented inflammatory statements.⁷ A university dean was fired for saying “hate begets hate,” while Kirk himself had said “it’s worth it to have a cost of, unfortunately, some gun deaths every single year so that we can have the Second Amendment.”⁸

This pattern reflects what Cambridge research identifies as “blatant political double standards” where people think moral foundations are more relevant when victims are groups they like but less relevant when the same groups are perpetrators. Both conservatives and liberals display this bias equally—conservatives show it for corporations and other conservatives, liberals for news media and other liberals.⁹

The speed of consequences also reveals institutional bias. Most terminations occurred within 24-48 hours, affecting academia, media, sports, and entertainment.¹⁰ Yet these same institutions rarely acted with similar speed when Kirk made comparably inflammatory statements about marginalized groups, suggesting that institutional responses are shaped by perceived political risk rather than consistent principles about harmful rhetoric.

Democracy Fund research found that 16-32% of Americans change their views on democratic norms based on which party is in power, showing what researchers call “democratic hypocrisy.”¹¹ This extends beyond individual responses to institutional behavior, creating systemic inconsistencies in how democratic societies respond to threats.

Historical patterns repeat across centuries

American history reveals remarkably consistent tribal responses to political violence across different eras. Even Lincoln’s assassination—now viewed as national tragedy—initially generated deeply partisan responses, with some Northern Democrats resenting Republican accusations of complicity and some Southerners privately celebrating.¹² A Massachusetts Democrat shouted “They’ve shot Abe Lincoln. He’s dead and I’m glad he’s dead.”¹³

The Kennedy assassination followed similar patterns despite different circumstances. Rather than turning against communists (the actual perpetrator’s ideology), American leaders “turned against America” itself, with journalists calling it evidence of a “sick society.”¹⁴ Many initially assumed a “rabid right-winger” killed Kennedy, not a communist, showing how pre-existing narratives shape interpretation more than facts.

Three distinct patterns emerge across historical cases: attribution bias (political groups consistently blame opponents regardless of actual perpetrator motivations), differential standards for violence (responses determined by victim’s political alignment), and institutional trust erosion (assassinations used to advance pre-existing political agendas rather than genuine reflection).¹⁵

The Gabrielle Giffords shooting in 2011 exemplifies modern tribal responses. Despite Jared Lee Loughner showing signs of mental illness with unclear political motivations, responses immediately fell along partisan lines.¹⁶ Democrats focused on “toxic political rhetoric” and Sarah Palin’s map with crosshairs; Republicans emphasized mental illness and rejected blame for political climate.

The psychology of motivated reasoning in crisis

West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center research reveals that political assassinations often serve as society’s “early warning signal,” revealing deep-rooted conflicts in social relations.¹⁷ But rather than prompting genuine reflection, they typically trigger what psychologists call “motivated reasoning”—using cognitive abilities not to find truth but to defend group positions and maintain group membership.¹⁸

Berkeley research found that when leaders invoke anger plus contempt and disgust, followers are more likely to devalue out-groups and respond with violence. Political violence is often catalyzed by predictable social events that trigger a sense of threat to shared identity.¹⁹ The Journal of Democracy analysis shows that between 2017-2020, 39% of Democrats and 41% of Republicans saw the opposing party as “downright evil.”²⁰

This creates cascades of group-think where individuals look to their group for cues about appropriate responses. Amy Chua’s research argues that tribalism makes every group feel endangered by others, causing them to “circle their wagons.”²¹ The result is that assassination responses serve group solidarity functions rather than democratic accountability functions.

Crucially, research shows that people who score highest on cognitive reflection tests are actually MORE likely to display ideologically motivated reasoning, not less.²² This suggests motivated reasoning isn’t about lack of intelligence but about protecting group identity—making even sophisticated Americans susceptible to tribal responses during political crises.

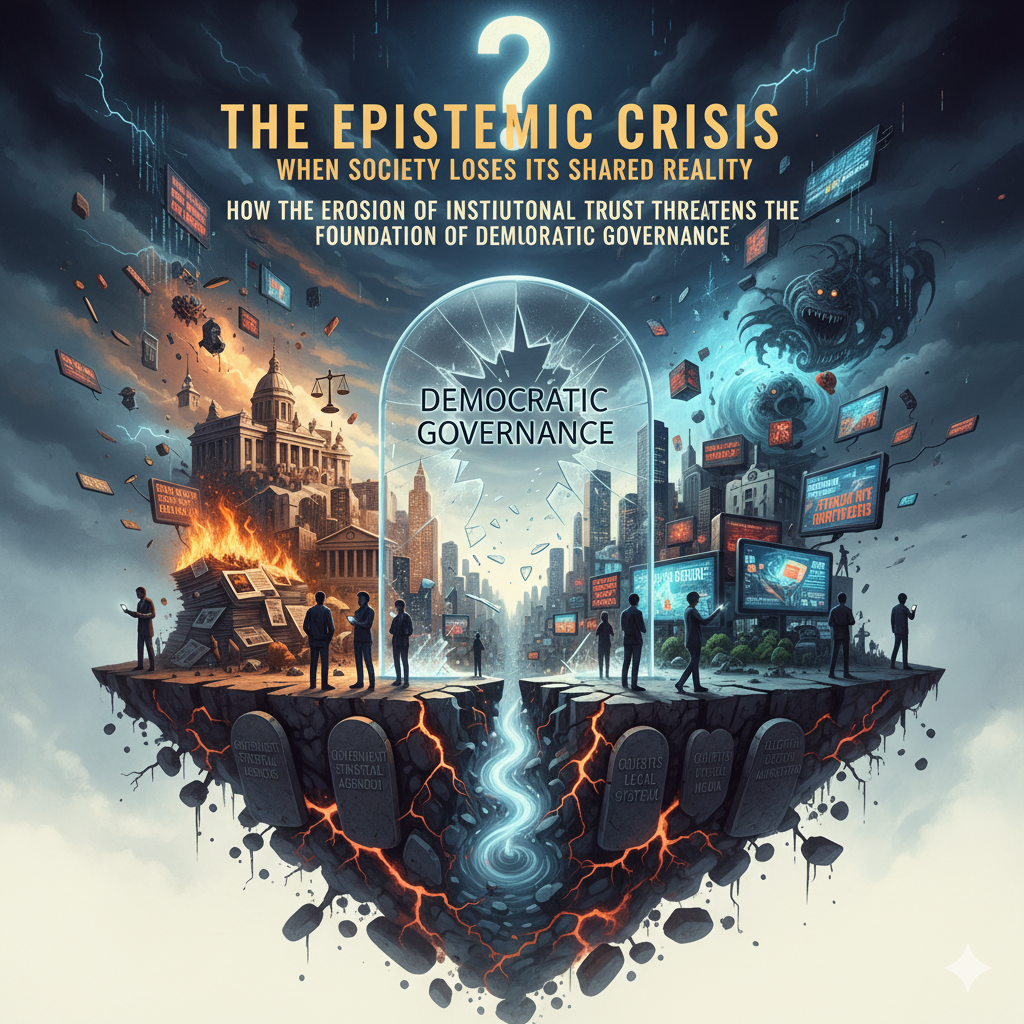

Systemic consequences for democratic discourse

The tribal logic of political violence creates what researchers call “lethal partisanship”—affecting 17% of Democrats and 24% of Republicans according to academic polling.²³ While most Americans reject political violence in principle, partisan identity strength predicts tolerance for violence against opposing groups. Harvard Kennedy School research indicates that it’s remarkably easy for leaders to reduce approval of violence simply by saying “don’t do that”—yet leaders often choose not to provide this clarity.²⁴

The consequences extend beyond individual responses to systematic erosion of democratic norms. When institutions apply consequences inconsistently based on political calculations rather than consistent principles, they undermine their own legitimacy. When media coverage follows partisan rather than professional standards, it accelerates democratic decay. When academic institutions prioritize political considerations over intellectual integrity, they damage their educational mission.

Research reveals that winner-take-all elections are particularly prone to violence, and two-party systems create more “us-them dynamics” than multiparty systems.²⁵ Americans have increasingly “sorted themselves into two broad identity groups” with fewer cross-cutting identities that historically reduced political violence.²⁶ This structural polarization makes tribal responses to political violence more likely and more dangerous.

Breaking the cycle requires institutional courage

The research suggests several interventions could reduce tribal responses to political violence. Cross-cutting identities—where people share characteristics with opposing partisans—reduce polarization, while “sorted” identities increase it.²⁷ Teamwork on common projects that join individuals on equal footing can counter tribalism.²⁸ Leaders play crucial roles in either inflaming or calming public responses.

But the most fundamental requirement is institutional courage—the willingness of institutions to apply consistent principles regardless of political pressure. This means universities, media organizations, corporations, and government agencies must develop and maintain standards that operate independently of tribal political calculations.

The alternative is democratic degradation through tribal logic. When consequences for speech depend on political affiliation rather than universal principles, when empathy extends only to political allies, when violence is condemned or excused based on partisan identity—democracy itself becomes another casualty of tribal conflict. The Kirk case illustrates real patterns that threaten the foundations of pluralistic self-governance, demanding responses based on democratic rather than tribal principles.

The choice is clear: Americans can continue allowing tribal loyalty to override democratic norms during political crises, or they can build institutions capable of consistent, principled responses to political violence regardless of partisan calculations. The future of American democracy may depend on this choice.

References:

- The Political Divide in America Goes Beyond Polarization and Tribalism – Kellogg Insight

- The Political Divide in America Goes Beyond Polarization and Tribalism – Kellogg Insight

- Why Tribe Divides Us – Annie Duke, Substack

- Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says – Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The case for partisan motivated reasoning – Springer

- Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says – Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Multiple news sources: MTSU assistant dean fired, Matthew Dowd Fired From MSNBC, Panthers fire staffer

- Charlie Kirk: “It’s worth to have a cost of, unfortunately, some gun deaths every single year so that we can have the Second Amendment” – Media Matters

- Political double standards in reliance on moral foundations – Cambridge Core

- Multiple sources documenting rapid firings across institutions (see reference 7)

- Democracy Hypocrisy: Examining America’s Fragile Democratic Convictions – Democracy Fund

- What the Newspapers Said When Lincoln Was Killed – Smithsonian Magazine

- What the Newspapers Said When Lincoln Was Killed – Smithsonian Magazine

- How JFK’s Assassination Changed American Politics – American Enterprise Institute

- The Causes and Impact of Political Assassinations – West Point Combating Terrorism Center

- 2011 Tucson shooting – Wikipedia; Shooting Fallout: Political Rhetoric Takes The Heat – NPR

- The Causes and Impact of Political Assassinations – West Point Combating Terrorism Center

- Motivated Reasoning and Political Decision Making – Oxford Research Encyclopedia

- What’s Driving Political Violence in America? – Greater Good Berkeley

- The Rise of Political Violence in the United States – Journal of Democracy

- Book review of Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations – Washington Post

- Ideology, Motivated Reasoning, and Cognitive Reflection – ResearchGate

- Who Advocates Political Violence? – Psychology Today; Radical American Partisanship – University of Chicago Press

- Political Violence in America: Causes, Consequences, and Countermeasures – Harvard Ash Center

- The Rise of Political Violence in the United States – Journal of Democracy

- The Rise of Political Violence in the United States – Journal of Democracy

- Various sources on cross-cutting identities and polarization reduction

- Various sources on cross-cutting identities and polarization reduction